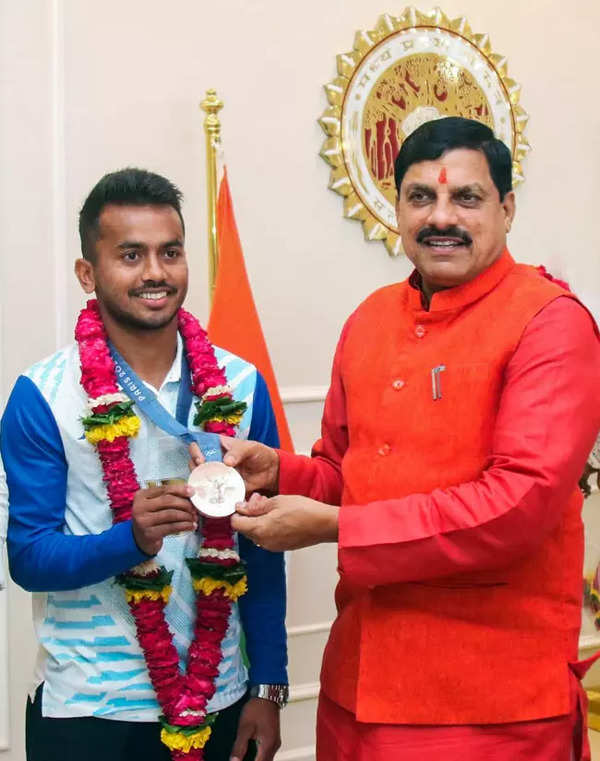

To cite a quick example before looking at the bigger picture, after Hockey India announced a prize money of Rs 15 lakh to each player for the bronze medal win at the Paris Olympics, Madhya Pradesh set the tone for the state governments with a Rs 1 crore reward for the midfielder from Itarsi, Vivek Sagar Prasad, also a Deputy Superintendent of Police in MP.

(Vivek Sagar Prasad with MP chief minister Mohan Yadav – ANI Photo)

That’s quite a healthy bank account in the name of a 24-year-old player from hockey — a sport in which coaches like Baldev Singh had to put their savings into buying a four-wheeler and convert it to accommodate an entire team and then himself drive players to matches across Haryana and beyond.

And that still sounds better than the crowd-funding that teams pre- and post-independence had to do in order to travel and compete at the Olympics.

This never-give-up belief highlights the connection the sport has to the masses. From the deep, almost inaccessible, corners of the country to the well-lit urban neighbourhoods and plush metropolitan housing societies, everyone in India celebrates major hockey triumphs. The connection further shows in the fact that despite the lack of resources, money and facilities, parents never pulled their kids out of dusty village hockey grounds.

Had that been the case, India would not have had a Rani Rampal, daughter of a cart-puller. Or a PR Sreejesh, whose father had to pull out all stops to somehow manage a sum of Rs. 15,000 for a goalkeeper kit so that his son doesn’t get taunted by his mates. Or a Neha Goyal, whose mother endured domestic violence, worked in a cycle factory and still backed her child to go and play hockey.

(Indian team on the podium at Paris Olympics after winning bronze medal – AFP Photo)

Unlike Pakistan, where lack of Olympic and World Cup medals after 1994 combined with poor governance sent the sport into a dark abyss, India swung into action post the era of erstwhile Indian Hockey Federation (IHF) to not just improve the administration in its new avatar as Hockey India, but also knock at the door of corporates and convince them to support the game.

Credit also goes to the Indian PSUs and government units for continuing to have hockey teams and thus create jobs that keep the players’ kitchen running while they focus on honing their skills — something that has evaporated across the border in Pakistan and proved detrimental to the youth’s interest in the sport.

The comparison with Pakistan is important because while India made an effort to adapt and evolve in the 21st century after years of denial, Pakistan didn’t. And the result is for the world to see.

Former HI president Narinder Batra’s alleged dictatorial ways of governance have often been condemned, but he deserves credit for bringing money into the sport since 2010. The support of the Odisha government proved to be a gamechanger as the state opened its coffers to sponsor the Indian national hockey teams across levels.

Corporate interest and investment gave birth to the Hockey India League (HIL) in 2013, and the Junior World Cup was conquered in 2016, which had a lot do with the supply chain put in place by the HIL, the benefits of which continued in the form of successive Olympic bronze medals — first in Tokyo, then Paris. However, the World Cup remains a horse that the Indian team is yet to saddle.

(Indian players doing lap of honour at Paris Olympics – ANI Photo)

The next World Cup is in two years’ time, when India will have another chance to make amends and give Ajit Pal Singh’s 1975 champions company. It’s a shame that India hosted two successive men’s World Cups at home and failed to even make the semis with the crowd behind them at jaw-dropping settings like Rourkela’s Birsa Munda Stadium and the Kalinga Stadium in Bhubaneswar. Now, they will have to do that on foreign soil — with Belgium and the Netherlands to co-host the 2026 edition.

The next two years will be crucial in more than one sense. The stability and consistency needs to be shown, by the players on the field and in the policies framed by the federation. Sticking to a process that has been successfully put in place by coach Craig Fulton should be a given, at least till the 2026 World Cup. Then the road to LA 2028 can be reassessed.

On the subject of players’ social security, it was a good step taken by HI two years ago, when it introduced the policy of annual cash incentives, where each playing member gets Rs 50,000 for every win registered by India’s senior men and women teams, while the support staff gets Rs 25,000.

With Olympic success, including the historic fourth-place finish by the women’s team in Tokyo, HI can take this stability to the next level and introduce central contracts, like in cricket, and base it strictly on performance and not reputation. It could mark the beginning of India becoming the first country to have full-time professional hockey players.

(PR Sreejesh, who retired after the Paris Olympics, climbed the goal-post after India’s bronze-medal win – ANI Photo)

In a podcast hosted by nnis on X (formerly Twitter) after India’s bronze medal win in Paris, former India captain Arjun Halappa urged HI to seriously consider this.

“I would love to see Indian players getting central contracts, where some financial assurance is guaranteed,” said the 2010 Asian Games bronze medallist, who added that he and his former teammates had raised the issue back in 2009.

“It is not about money, it is about the effort we (players) are putting in for the whole year for the nation. If central contracts come in, it will be a big game-changer for the sport of hockey. It is one thing I want to see. We fought for it in 2009-10.”

Halappa said it would end the plight and dilemma of a young hockey player in India.

“Hockey players come from poor backgrounds mostly, where parents struggle to make ends meet; there are neither studies, nor money. If they go on to play for India (senior), then they can hope of securing a job, otherwise they find themselves on the crossroads,” Halappa, who was part of India’s victorious 2001 Junior World Cup-winning team, said.

(Manpreet Singh, left, and Mandeep Singh being welcomed on arrival at their hometown Mithapur – AFP Photo)

HI may argue that the jobs players secure as India internationals lend stability to their hockey careers. But the federation must not miss the point that it doesn’t make them professional players, which may not be a trend in the sport across the world but something not many players will oppose. HI can lead the way in this with the momentum of two successive Olympic medals for the first time in 52 years and more money in the bank compared to the national federations of other leading hockey-playing nations.

A grade-based central contract system will motivate players and improve competition for places even further because better, consistent performers will be in the higher grade and thus earn more.

Above all, it can bring a change in the age-old thought process of securing a job by becoming an international player. A central contract, offering players a chance to earn more, can take its place.

However, it can’t be debated that the generation of players part of Indian hockey’s journey since 2010 have been well taken care of. They have been appropriately rewarded, for five years in HIL (2013 to 2017) and then for their remarkable return to the Olympic podium in Tokyo and staying there in Paris. It’s the next crop of players, someone like Sanjay, Sukhjeet, Abhishek and Raj Kumar Pal, that HI will have to make feel secure about their future as an India player.

(ANI Photo)

The second edition of the HIL, expected to roll out by the end of this year, will once again lay the foundation of that security and making players hockey professionals. Hopefully, the league will also give India more Mandeep Singhs that go on to become Olympic medallists and re-establish the supply chain that got snapped in 2017. And a central contract getting into the mix will make these players ‘fearless’ in every sense.

As a hat-trick of Olympic medals beckons, it could be a game-changing start to the post-Sreejesh era on the road to LA 2028.